Interviewed in March of 2016 by Andrew Houle

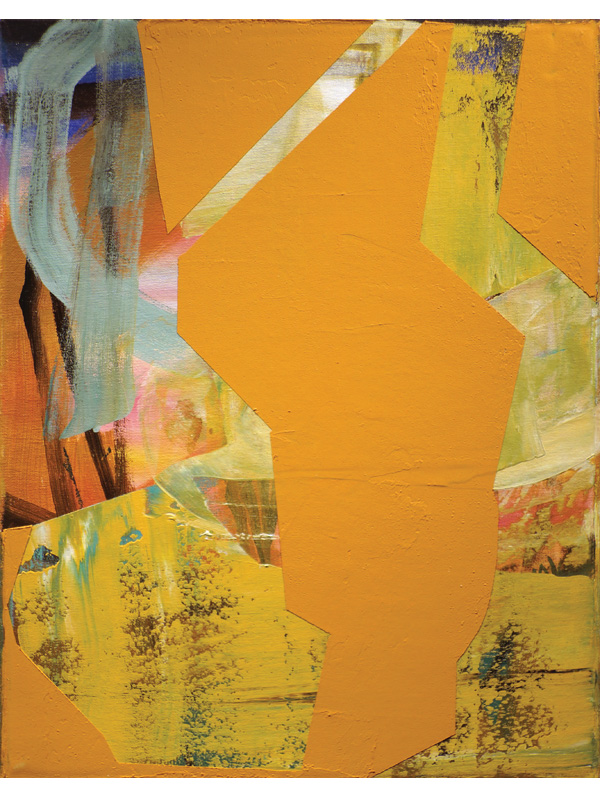

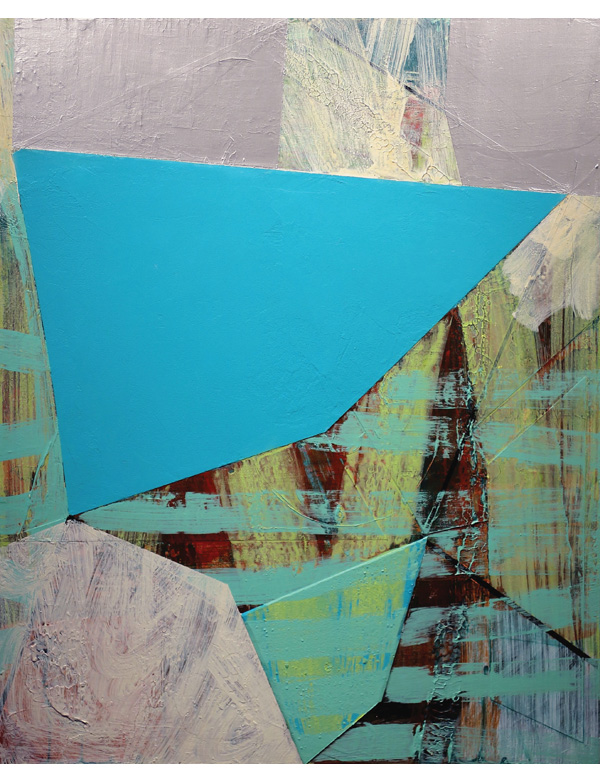

ANTHONY FALCETTA

Hometown: Manchester, CT

Current town: Beverly, MA

Website: Click Here

1.) We’re so thrilled to finally have you in the pages in Chroma. Can you first give our readers a little background on where you’re from, and the formative years of your education as an artist?

Thanks for including my work! Glad to be here.

I grew up in Manchester, Connecticut. It used to be the home of a major silk and textile manufacturer from about 1830 to the 1950s, but that industry had died off by the time I was born. All that was left was its infrastructure... railways, former millworker houses, smokestacks and these massive brick mill buildings, mostly empty. Some of my earliest memories are of the colors and geometries of those places, and as a kid, I used to ride my bike through these decrepit spaces and think about time and history and change. It definitely prepped me for a love of tactile materials, and physical changes or destructive editing in my work, but there was also this sense of time making things unrecoverable, and of layers of history that needed to be read all at once, then selectively, in order to make sense. That's stuck with me my whole life, and is discernible in my work even if I'm not pointing to it directly, I think.

2.) In the simplest of terms would you describe yourself as an abstract painter? At times the titles that describe the work of an artist leave a lot to be desired. How would you describe your work to someone who has never seen it before?

I’d be fine with just describing myself as a painter or an artist who makes painterly objects. The term "abstract" has been bent and folded and stuck to so many kinds of imagery, appropriately and not, that I'm not sure people actually get an image in their minds when they hear it anymore. I tell people that my work comes from looking at the patterns, shapes, forms, and colors of landscape and my surroundings, but that I try not to make "pictures of" any of it. I'm making objects that might remind, or carry information about, or rhyme with some of those sources -- but to name them outright would imply a way the work should be seen or used, and for me, that's no fun. If someone had never seen my work before, I'd use a lot of words like "gestural" and "textured" and "mixed-media" and "geometric"… then send them to my website and wish them happy clicking.

3.) Throughout your educational journey as a painter starting at Gordon College and later at Mass College of Art & Design, who would you say had the largest impact on your work leading up to present day? Was there an instructor or mentor that stands out to you as a pivotal relationship in your path to becoming an artist?

I came to college the first time around thinking I was going to be a writer. I was always an articulate kid and learned to put everything into words early on. But there was this nagging feeling of “never quite getting at” something when I had to write about it. I could do jitterbugs and tangoes with words -- but in the end, words are really just symbols. We make letters using lines and curves, to represent certain sounds we make with our voices, then we combine these little abstractions into words, and then the words get used to name and categorize and respond to and explain the whole world. Eventually, we forget to see what the words were pointing to in the first place: the names become the things for us. I'd had this other creative side to me that had to do with space and found objects and combining things to make other things -- but expressing myself had always involved putting words together, so the other tools tended to get left in the toolbox.

About halfway through my English BA, I met painter and teacher Bruce Herman, who gave a slide talk in one of those survey arts/music/drama courses that are designed to make students "more well-rounded" before they give up on creative stuff and start getting pragmatic about life. Bruce brought several of his large paintings along so we could all see them up close, and hearing him talk about his path as an artist, and realizing that these very physical, very mysterious objects were containers for his actual experiences and inner life -- it was like I heard this audible click. I ended up gradually taking more and more of the school's visual art courses, and would have probably finished with a dual degree if the college had offered an art major yet. That didn't come until after I'd graduated, so I took a minor instead.

Several years later, after writing some well-intentioned poetry, making some tentative art, and trying to figure out whether the whole argument between the two was really just an elaborate form of fooling myself, I went back to school and earned a BFA in painting at MassArt. It was a way of challenging myself to work and live and think as a visual artist, and maybe fail my way out of it if necessary. That decision to commit to making art has really shaped the last two decades of my life.

4.) Intersecting lines, boundary defining shapes, layers upon layers of transparency (or opacity), slivers of color, and raw texture are all major forces that culminate in your work. As you settle in on each new piece, large or small, what is a natural starting point for you, and how does that determine your decision making as you work?

I had a brief but intense love affair with Jasper Johns while I was at art school... his work and his writing really taught me the value of taking a thing, doing something to it, looking at the results, and letting that determine what the next thing you do should be. I guess all artists follow that process in some way, but with Johns, it was also a philosophical thing, working with "things the mind already knows" like flags and targets and numbers and such. I picked up on the kind-of-perverse thrill of carefully building and revising a thing without (maybe) ever intending to make it mean something or represent something. But I was surprised and excited when I began to realize that the process itself was one of finding sense. The final object could really look like whatever, but the processes of shaping it were just as significant as the product for me... sometimes more so.

In my own work, I start with some seriously shitty painting; I think of it as "getting my AbEx out." This is done mostly to put something down on the surface that will require a next move. Very rarely does anything survive from start to finish in my paintings... except as ghosts in the matrix of the work, that show their shapes in the responses they provoked. I think about and respond to dualities a lot; shiny demands matte, line wants mass, thick needs thin, and beautiful secretly craves some ugly. When the thread I've been following in a piece suddenly breaks off, I know I can always respond to something else in the work by smushing it against its opposite. (Whether that move stays in the piece then becomes the question.) What a viewer sees as my finished work is usually just the point where it spun down to a pause. I have some innate senses of order and proportion and balance working in my favor that can help a piece feel complete, but I know how tenuous balance is, so I never really trust that feeling of finish for long. Balance is a verb -- a process of holding opposing forces in tension, and it takes the next painting and the next to keep that going.

5.) The most commonly sold artist canvas sizes are 16” x 20” and 18” x 24”. A nice easily managed scale that fits conveniently on just about any easel. Earlier in your career a lot of your paintings came in generally two sizes; huge and “I think we’re gonna need a bigger wall”, with dimensions coming in around roughly 5” x 5”. What is it like approaching a canvas with such a vast surface? Are the scale and physicality intimidating or conversely freeing with so much room to work with?

Yeah, I used to work larger... 65" x 65" was the width of my arms, so I started there. But really, the largest piece I ever finished was only 72" x 60", so you may be overselling this scale thing. There was a time early on when that kind of room to run really did feel freeing, and I may go back there sometime, who knows. The process with those larger pieces was faster and looser, and it felt like a dialogue with the "entity" of the painting: who are you, what do you want, what happens if? At that time, I think I needed to be confronted by something physically my own size or larger, and throw myself in, then paint my way out. Keeping those opposing forces in tension definitely feels like more of a battle on a larger surface, but I learned some important lessons from those big pieces that help me do the same kind of thing on a smaller scale now.

It sounds dumb, but I got tired of renting trucks and vans to lug my big paintings everywhere -- and I found that, no matter how large the pieces were, there were always these specific little portions that called to me because of their textures or color interactions or something. I decided to deal with both situations by trying to make smaller paintings that felt big. In a way, I'm stubborn enough that I refuse to be stuck on an idea past a certain point... even if it was a good one I came up with myself. The "need" to work large -- like the "need" to use oil paint or the "need" to start paintings with drawings -- began to feel like a crutch or a false requirement for making good work, so I had to do the opposite and see what came of it. These days my work ranges from 8" x 10" pieces on paper, up to 40" x 40" panels and canvases, which is the size that fits most conveniently in the family wagon.

6.) Most of your paintings and drawings media-wise consisted of oil paint and oil bars up until recent years. What prompted such a major switch in mediums to acrylics? Safety or health issues? Ventilation?

My son was born in 2008, and since my wife was just starting her first tenure-track job teaching literature, it made sense for me to take on the day-to-day parenting. It quickly became clear that I was going to have to put down my brushes for a while to focus on being a dad -- which continues to be an unbelievably rich experience -- and to renovate the house we'd just bought. When I was able to get back to painting, my studio space was in our basement, with a forced-air heating system that recycled whatever fumes were down there into the rest of the house. Not wanting to gas myself or my family, I opted to switch to acrylics.

7.) Putting aside the obvious difference with drying times (which these days can be pretty much neutralized), what are the aspects you find advantageous to each medium; oil and acrylic? Is there a physicality to one that you can’t generate with the other i.e., glazing, viscosity, texture or luminosity?

Oil paint is sublime in a way acrylic can't be. It's got the potential for tenderness and breath and goo and crust in ways acrylic will (probably) never achieve. Oils are unparalleled for depiction -- they accumulate on a flat surface and take and give backlight in a way we instinctively recognize from the actual, tangible world. They're also unpredictable enough to give really incredible chance effects if used in a more process-driven or physical way. But I've been surprised at the things acrylics can do that oils don't have the temperament for. Acrylics are pretty much bulletproof once they're dry (and when they're dry, they're dry all the way down). They're forgiving... no need to worry about thick over thin, and a layer can be wiped off with a dish sponge if you catch it when it's still damp. They mix with a huge range of water-based materials (like the gypsum wall-patch I use), and they can be combined with gels and pastes and fluid mediums to get nearly any kind of effect. They're flexible. They can be adhesive or repel water... they can be made opaque or completely transparent without losing integrity.

After switching over, I really had to learn to stop expecting acrylic paints to act or look like oils; stop simulating what I knew, and let this very different material do the things it was best at. It took awhile, but I think in the process I’ve been able to create a physical and tactile language for my work that lets me say a lot more. I feel like the possibilities are only limited by how "out there" I want to get with the medium.

8.) With all the mark making and layers to your paintings, it's obvious that the good ol’ fashioned paint brush is just one of many tools employed while you’re creating. What other artist’s tools and even common household items do you find yourself utilizing while painting? Brayers, palette knives, or something no one would ever guess? Give us the goods. We’re looking for serious industry secrets here.

My favorite tools are really pretty mundane: a variety of big palette knives (pastry chefs would recognize some of these as "offset spatulas"), drywall taping tools, silicone scrapers, and those horrible chip-brushes from Home Depot that frizz out and drop a bunch of bristles when you first use them. I also have the usual collection of "fine art" brushes for when I need that certain painterly flavor in the work, but there are entire weeks when I have to remind myself to use them. I use about a metric ton of masking tape to get clean geometric shapes, and lately, I've been experimenting with relief monotype printing, so that gets in there too. Basically, if it solves a problem or satisfies an impulse in the context of a piece, I'll give it a try and then see how it sits. I think about Robert Rauschenberg's work a lot when I'm doing something potentially sketchy to a work in progress. I think he had a couple of kinds of bravery as an artist: first, the courage to put something potentially ridiculous into a piece -- and then the courage to leave it there.

Let's talk surfaces; cradled panels, stretched canvas or a nice heavy paper? Knowing you work on all three listed… do you have a preferred or favorite surface?

I've mostly been painting on panels the last couple of years because I've been using gypsum wall-patch compound and wanted to get the hang of applying it in different ways. Panels don't flex the way canvases do, which allows me to use thicker applications without worrying about cracking. But canvas never quite went away, and in fact, I've been moving back toward small ones lately. They're lighter and take up less room, and I'm finding my mixed-media approach still works pretty well, at least on a small scale. "Paper" for me usually takes the form of scrap framers matboard, or I buy this resin-treated paper that feels sort of like a brittle card stock. I made some paintings on paper awhile back, but ended up either having to frame them or mount them to panels, so these days I usually just paint directly on a support and skip the paper part. In general, I find I spend more time than I like thinking about the "body" of a piece -- whether or how to frame it, what support to paint it on, or how I'm going to store more finished work in my ever-shrinking studio space.

9.) You’ve recently been accepted into a four-week artist residency at the Vermont Studio Center up in Johnson, VT. (Congrats!) Can you tell our readers about how this program works and what kind of requirements are there to applying?

Vermont Studio Center is located on a small river in a small town in rural Northern VT, so it's peaceful, beautiful and a real retreat. It provides lodgings, a private studio and three meals a day for the 50-60 artists and writers who are doing residencies at any given time. Residencies can be anywhere from one to four weeks, or more if you want to pay for the time, but the conventional wisdom is that at least two weeks is a good start. The requirements are pretty simple: be a working artist or writer who wants to spend focused time on your art in a setting where it's not only encouraged but fully supported. I sent an application to their review panel, who chose me and were nice enough to also give me a small grant based on the merits of my work. I raised the rest of my residency fee with a crowdfunding campaign that turned out to be a huge success. There are always grants and awards available on a rolling basis, from private organizations as well as VSC, that can help offset the cost of a residency.

10.) With a campus setting of over 50+ artists and writers residing at VSC throughout your tenure, what kind of personal goals are you setting for yourself upon arriving? Could this also be an experience where sometimes having “no plan” could be the best plan with the potential for so many collaborative projects?

It's been a busy year, and I'm looking forward to moving at a slower pace, and making things in a setting where I can work longer hours or at different times of day than I'm used to. I'm also really excited to meet the other artists and writers who will be at VSC during my stay. I've heard from friends who have done residencies there, that they formed friendships which are still vital even years later. It seems like the kind of place where conversation, looking, listening and thinking about others work counts for as much as doing one's own thing. As far as a plan or goals for my work... I'm going up with lots of blank surfaces, lots of materials, and a few really persistent ideas that have been evolving over the past couple of years. I guess I'll start with that and stay open to what happens next. At worst, I'll have a pile of solid work that feels familiar, and hopefully a lot of good experiences -- but there's definitely the potential for things to get all weird and awesome in ways I won't see coming. A next level or a new kind of clarity. I'll keep my eyes open for it.

11.) Lastly, something we love asking our featured artists is who do they think is an artist everyone needs to know about. Whether a painter, musician, writer, anything goes. Who you got and why?

Oh man, where to start. We're in an incredibly exciting time for art, and for abstract painting in particular, so there are dozens of artists I follow online, and a bunch I'm really fortunate to be friends with in person. Then there are the ones from the art-history books -- my influences, the artists whose work I've hated and learned to respect, the ones I secretly wish I was, and even the ones I don't care about no matter how much I know I'm supposed to. And music is so crucial to my work, I don't think I could ever paint in silence. I don’t think I can pick just one or two of these artists whose work and sounds have meant so much to me. (I can say there’s been a tremendous amount of Bowie in the studio since January, though.)

Here’s something I’d share with anyone working as an artist: a piece of writing that keeps on unpacking itself in my work but also for the rest of my life. It's a fragmentary list that painter Richard Diebenkorn scribbled to himself sometime during his studio practice and kept tacked to his wall, called "Notes to Myself on Beginning a Painting." His work has had a huge impact on my thinking as well as my working methods, and this list has become almost meditative to me over time, like a collection of Zen Kōans. I'll leave it to you to Google the whole thing, but it starts off like this:

"1. attempt what is not certain. Certainty may or may not come later.

It may then be a valuable delusion."

I think my work lives in and explores that kind of uncertainty in many ways, and I appreciate Diebenkorn not just for the magnificence of his work, but for the clarity and persistence of his mind as he kept it open to his work. Hopefully his notes to himself will prove as useful for someone else out there as they’ve been for me.